Beating Burnout: Understanding NHS working conditions, workforce retention and implications for patient care

By Vicky Morley, Senior Clinical Advisor

Work-related stress and burnout remain widespread across the NHS, according to the latest staff survey (1), with many NHS staff feeling undervalued and overstretched.

These findings align with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2024 annual leavers survey, which revealed that half of all nurses leaving the profession are doing so earlier than planned, with a worrying increase in those departing within just five years of joining (2, 3). While NHS staff cite various reasons for leaving, a 2024 report by The Nuffield Trust found that workplace stress and understaffing ranked among the most significant factors—coming out ahead of pay concerns (4).

The purpose of this article is to promote awareness around healthcare professionals’ working conditions and the cognitive overload they are facing, discuss how this impacts the well-being of both patients and care teams, and present a way digital solutions, specifically, a mobile communication platform, can improve clinical working environments and patient care.

A call for here-and-now action

Following the prolonged industrial action by NHS staff between 2022–2024, the healthcare system continues to recover from the most disruptive labour disputes in its history. The walkouts by nurses, ambulance workers, junior (now resident) doctors, and consultants highlighted critical issues surrounding excessive workloads, chronic stress, widespread burnout, and significant erosion of real-term pay. Although pay agreements have since been accepted, the British Medical Association (BMA) cautions that there is a long way to go to ensure healthcare professionals are neither underpaid nor undervalued in the future (5).

In June 2023, the NHS published its long-term workforce plan (6), commissioned by the UK Government, to address the expected shortfall of staff by 2036/37.

Whilst generally welcomed, the plan has received criticism regarding its ability to deliver immediate transformative solutions to urgent healthcare challenges, particularly the retention of medical professionals and the mitigation of workplace burnout among frontline staff (7). Furthermore, a report by the National Audit Office (2024) questions the plan's optimistic modelling assumptions, particularly given the need for substantial policy reforms and significant financial investment to achieve its objectives (8).

Emergency care under extreme pressure

Perhaps positioned most on the front line, are those clinicians working within emergency care. Urgent and emergency care services regularly make the headlines for being under extreme pressure, with overstretched A&E departments recording unacceptable waiting times and ambulances left queuing for hours at the door.

Within England, published statistics show that in 2024, attendance at A&E departments was 20% higher than ten years ago (26.3 million attendances), with winter again proving notoriously difficult for those providing emergency care (9).

Additionally, A&E care has seen a sharp decline in public satisfaction (10, 11). Within the 2023 survey on British Social Attitudes (12), 37% of respondents reported being very or quite dissatisfied with A&E provisions. This is the second highest level of dissatisfaction in a single year (along with 2022) since the question on A&E services was first asked a decade and a half ago (13).

At the start of 2023, the NHS published its 2-year delivery plan for improving urgent and emergency care services (14), aimed at increasing capacity, improving patient flow, and speeding up hospital discharges. However, as of early 2025, performance still failed to achieve the revised 78% target for 4-hour wait times carried over into the 2025/26 priorities and operational planning guidance (15). This highlights the persistent gap between policy objectives and operational realities whereby, despite strategic ambitions on paper, those working within emergency departments remain under immense pressure.

The challenges of maintaining concentration on critical care tasks

As healthcare organisations strive for greater efficiency in their high throughput emergency departments, one impact on clinicians is the ever-increasing requirement to deliver patient care in the midst of workplace interruptions.

"Clinicians commonly experience more than 10 work interruptions per hour"

(Teigne et al. 2023)

Work interruptions can be defined as breaks in the sequence of task performance, causing a temporary pause of task continuity (16).

Although some task interruptions are necessary to alert colleagues to problems, most are recognised within the literature as detrimental and over half as avoidable (15). Within busy hospital settings, frequent interruptions negatively impact productivity, focus, decision-making, and information transmission and increase error risk (16-18).

While managing complex information and triaging ongoing priorities, clinicians must navigate through the disruption of regular pages, texts, and phone calls, alongside the constant beeps of patient monitors or call bells.

When these technical work interruptions are coupled with human interruptions from colleagues and interprofessional team members and by patients and their relatives, clinicians must decide where to divert their time and efforts. This makes maintaining concentration on critical care tasks challenging and leads to a higher probability of tasks being delayed or forgotten altogether (19).

A growing multitasking epidemic

Another source of interruptions to the workflow is the requirement for nurses and doctors to often handle multiple activities at once. Multitasking has long been recognised as a key skill for emergency department providers.

"It can take up to 25 minutes to regain focus on a task after a disturbing context shift"

(Westbrook et al. 2018)

Nurses multitask as they manage patient care and communicate with healthcare professionals simultaneously. They may discuss a patient with another clinician while entering data into the EHR and asking the patient about pain while administering medication.

The ability to remain focused on essential nursing activities is paramount for patient safety. However, due to workforce shortages, nurse-to-patient ratios continue to increase, leading to a greater volume and complexity of multitasking (20).

Cognitive overload: a silent threat to patient safety

Clinicians can become overwhelmed when multitasking with high amounts of information from multiple sources, making it difficult to have adequate working memory to focus on patient care tasks (21).

Our working memory allows for the temporary storage and active maintenance of task-related information whilst performing the task in the face of distractions. However, too much in the way of interruptions and multitasking makes increased and unsustainable demands on working memory (22).

Cognitive overload occurs when a person's working memory is overwhelmed with information, leading to negative impacts on their well-being and potential errors that can affect patient safety.

"Cognitive overload is a cause in 80% of medical device user errors and being distracted plays a role in nearly 75% of medical errors"

(Collins 2020).

The impact of cognitive overload on medication errors is a particular area of concern, especially when more than 237 million medication errors are made every year, costing upward of £98 million to the NHS and more than 1700 lives (23). Interruptions and multitasking are frequently found as causal factors for medication errors (18, 24).

Similarly, cognitive overload associated with having to remember verbal patient updates has been found to worsen diagnostic decisions making (20).

It is, therefore, imperative that healthcare leaders look to understand patient safety from the perspective of interruptions, multitasking and their associated cognitive burden and how best to manage these challenges in the context of their specific work environments.

Creating work environments where clinicians can flourish

How can targeted interventions limit interruptions in healthcare settings to help doctors and nurses thrive?

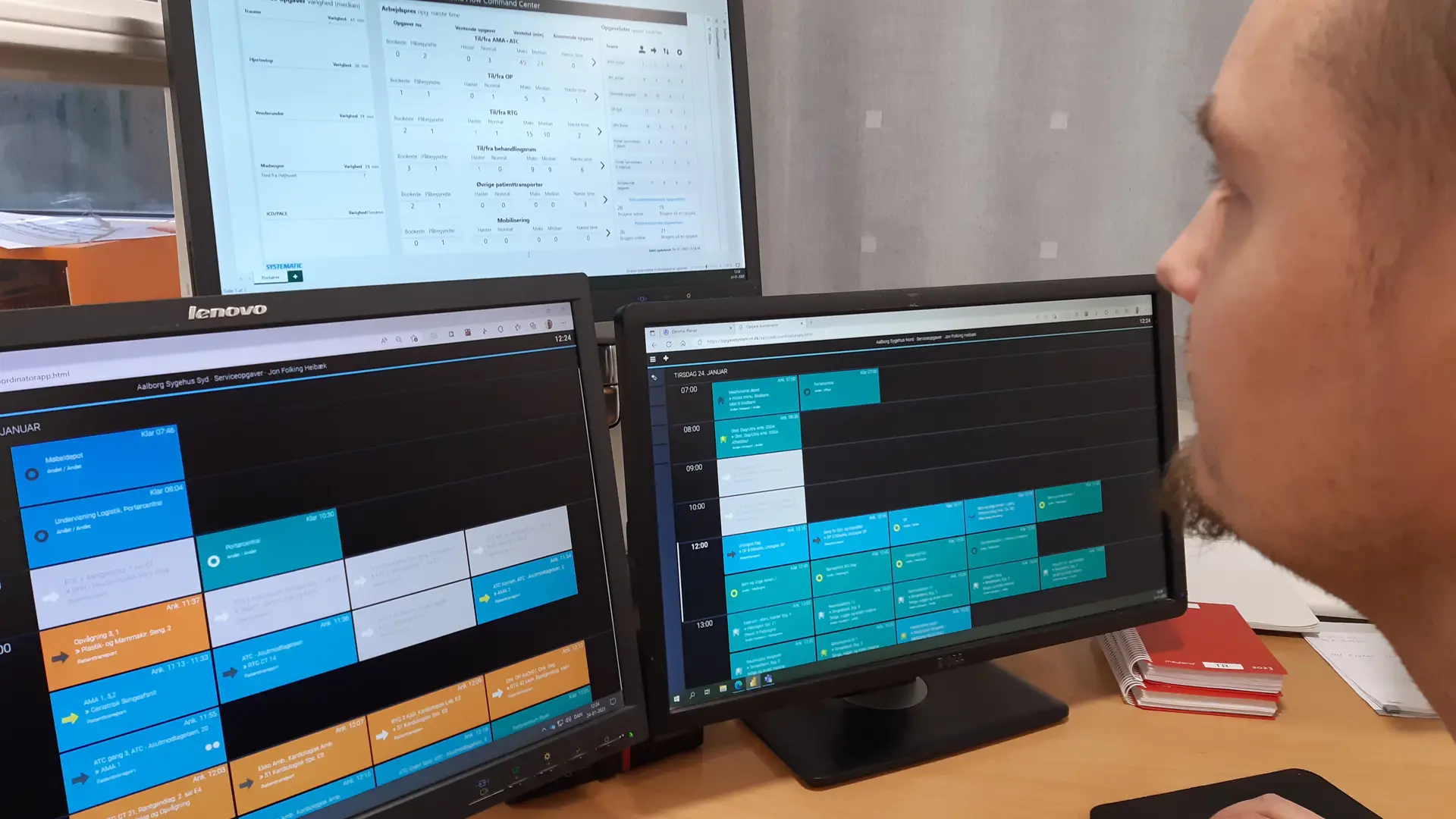

One practical solution involves improving the efficiency of communication channels between care providers. Implementing digital technologies can help information and communication flow smoothly across organisations, people, and places, bringing benefits for both patients and staff, including improved patient safety, reduced costs, and time savings (25).

Communication and collaboration platforms assist clinicians by minimising the amount of information which needs to be stored in memory and preventing the bombardment of interruptions, acting to reduce the cognitive burden on the caregiver, simplifying care delivery and increasing patient safety (26).

Streamlining in this way, also replaces interruptive communication patterns, such as face-to-face or telephone contacts, with less obtrusive asynchronous messaging to coordinate patient care.

This enables efficient, real-time communication to be shared through patient context messaging, differentiated by situational urgency priority, to the right caregivers who can be easily dentified irrespective of their location on a single, interoperable platform and thus makes it easier for clinicians to perform their roles more effectively.

Modifying operational and communication processes within hospitals, and in particular emergency departments, provides a proven opportunity to improve productivity, flow, and patient experience. It also increases the perception of job discretion, autonomy, and controllability among clinicians (16, 17).

Recognising that the current workforce and patient demand challenges within the NHS are unlikely to be resolved in the immediate term, there is a real need to do things differently rather than continuing as we are.

Great gains could be made from healthcare leaders analysing the efficiency of their communication workflows to gain insight into how existing processes could be done in a better way.

References

- NHS England (2025) NHS National Staff Survey 2024. Available at: https://www.nhsstaffsurveys.com/results/national-results (Accessed 13 March 2025). Nursing & Midwifery

- Council (NMC) (2024) NMC Register Leavers Survey. Available at: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/data-reports/july-2024/annual-data-report-leavers-survey-2024.pdf (Accessed 13 March 2025).

- Nursing In Practice (2024) Major rise in nurses quitting early putting NHS reforms at risk. Available at: https://www.nursinginpractice.com/latest-news/major-rise-in-nurses-quitting-early-putting-nhs-reforms-at-risk/ (Accessed 13 March 2025).

- Nuffield Trust (2024) The NHS Workforce in Numbers. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/the-nhs-workforce-in-numbers#toc-header-0 (Accessed 13 March 2025).

- British Medical Association (2024) Junior doctors in England vote to accept pay offer. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/bma-media-centre/junior-doctors-in-england-vote-to-accept-pay-offer (Accessed 3 March 2025).

- The Kings Fund (2023) The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan explained. Available at: The NHS Long Term Workforce Plan explained | The King's Fund (kingsfund.org.uk) (Accessed 22 January 2024)

- Nuffield Trust (2023) NHS Performance Tracker. Available at: NHS performance tracker | Nuffield Trust (Accessed 22 January 2024).

- National audit Office (2024) NHS England’s modelling for the Long Term Workforce Plan. Available at: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/NHSE-modelling-for-the-LTWP-Summary.pdf (Accessed 3 March 2025).

- NHS England (2024) Hospital Accident & Emergency Activity, 2023-24. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-accident--emergency-activity/2023-24/summary-report (Accessed 3 March 2025).

- CQC (2024) Urgent and Emergency Care Survey 2023. Available at: https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/surveys/urgent-emergency-care-survey (Accessed 3 March 2025).

- The Kings Fund (2023) Public Satisfaction with A&E at an all-time low: reflections of an A&E doctor. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/blogs/public-satisfaction-ae-reflections (Accessed 23 January 2024).

- National Centre for Social Research (2023) Public attitudes to the NHS and social care report. Available at: https://natcen.ac.uk/publications/public-attitudes-nhs-and-social-care (Accessed 3 March 2025).

- The Kings Fund & Nuffield Trust (2024) Public satisfaction with the NHS and social care in 2023 - Results from the British Social Attitudes Survey. Available at: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-03/BSA%20Survey%202023_FINAL.pdf (Accessed 3 Mach 2025).

- NHS England (2023) Delivery plan for recovering urgent and emergency care services. Available at: NHS England » Delivery plan for recovering urgent and emergency care services (Accessed 22 January 2024).

- NHS England (2024) 2024/25 priorities and operational planning guidance. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024-25-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance-v1.1.pdf (Accessed 3 March 2025).

- Abdelhadi, N., Drach-Zahavy, A. and Srulovici, E. (2022) ‘Work interruptions and missed nursing care: A necessary evil or an opportunity? The role of nurses’ sense of controllability’. Nursing Open, 9, pp.309–319. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1064 (Accessed 23 January 2024).

- Teigne, D. Cazet, L. Birgand, G. et al. (2023) ‘Improving care safety by characterizing task interruptions during interactions between healthcare professionals: an observational study’. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 35(5), pp. 1-9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzad069 (Accessed 23 January 2023).

- Bower, R., Coad, J., Manning, J. et al. (2017) 'A qualitative, exploratory study of nurses’ decision-making when interrupted during medication administration within the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit'. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 44, pp. 11-17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.012 (Accessed 23 January 2023).

- Sanderson, P., McCurdie, T. and Grundgeiger, T. (2019) ‘Interruptions in health care: assessing their connection with error and patient harm’. Hum Factors J Hum Factors Ergon Soc, 61, pp. 1025–36. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1177/0018720819869115 (Accessed 23 January 2023).

- Kim, Y., Lee, M., Choi, M. et al. (2023) ’Exploring nurses' multitasking in clinical settings using a multimethod study’. Sci Rep 13(5704). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-32350-9 (Accessed 23 January 2023).

- Collins, R. (2020) ‘Clinician Cognitive Overload and Its Implication for Nurse Leaders’. Nurse Leader 18(1), pp. 44-47. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2019.11.007 (Accessed 22 January 2023).

- Westbrook, J., Raban, M., Walter, S. et al. (2018) ‘Task errors by emergency physicians are associated with interruptions, multitasking, fatigue and working memory capacity: a prospective, direct observation study’. BMJ Qual Saf. 27(8), pp. 655-663. Available at https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007333 (Accessed 23 January 2024).

- BMJ (2020) ‘237+ million medication errors made every year in England’. Available at 237+ million medication errors made every year in England | BMJ (accessed 23 January 2024).

- Yen, P., Kelley, M. and Lopetegui, M. (2018) ‘Nurses’ Time Allocation and Multitasking of Nursing Activities: A Time Motion Study’. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018, pp. 1137–1146. Available at: Nurses' Time Allocation and Multitasking of Nursing Activities: A Time Motion Study - PubMed (nih.gov) (Accessed 23 January 2024).

- The Kings Fund (2022) Interoperability is more than technology: The role of culture and leadership in joined-up care. Available at: Interoperability is more than technology | The King's Fund (kingsfund.org.uk) (Accessed 24 January 2024).

- Austin, E., Blakely, B., Salmon. P. et al. (2022) ‘Technology in the emergency department: using cognitive work analysis to model and design sustainable systems’. Safety Science, 147, pp 1-12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105613 (Accessed 24 January 2024).

Latest cases

Our solutions and services make a difference to our customers. Take a look at our cases and find inspiration in the benefits others have realised.